‘Did you hear the birds? In this wind they’re still singing!’ Outdoor psychotherapy -A trauma informed perspective.

by Joanne Hanrahan

“The best remedy for those who are afraid, lonely, or unhappy is to go outside, somewhere where they can be quiet, alone with the heavens, nature, and God…. And I firmly believe that nature brings solace in all troubles.” These words from Anne Frank (1954: 136) may have always rung true for many people, however the current global pandemic has made them more relevant for all. Societies worldwide are now appreciating more than ever before the freedom, relative safety and ease that being outdoors brings. Here in Ireland, there has been a huge increase in the number of people sea swimming, exer•cising outdoors and simply spending time in nature. While this has had a positive impact on physical wellbeing and reduced the risk of contracting Covid-19, what are the benefits of spending more time in nature and what teachings, and possibilities can this bring to the profession of psychotherapy? This article will address these questions through a mix of personal reflection on my own clinical and academic experience of outdoor psychotherapy, client case studies and drawing on wider theoretical understandings in areas such as body orientated psychotherapy, trauma informed approaches, polyvagal theory, and ecotherapy.

Nature and wellbeing

Frequently cited works, most of which were published over thirty years ago by Wilson (1984), Ulrich (1984), Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) and Kaplan (1995) set the scene for what is now an “overwhelming body of evidence” (Sempik et al., 2010: 118) demonstrating that the natural environment is beneficial to health and wellbeing. Wilson’s work on the biophilia hypothesis proposed that the tendency of humans to focus on and to affiliate with nature and other life-forms has, in part, a genetic basis. Ulrich’s seminal study also proposed that a view through a window may influence recovery from surgery, while Kaplan and Kaplan’s attention restoration theory (1989) and Kaplan’s stress recovery theory (1995) link exposure to natural environments and recovery from physiological stress and mental fatigue.

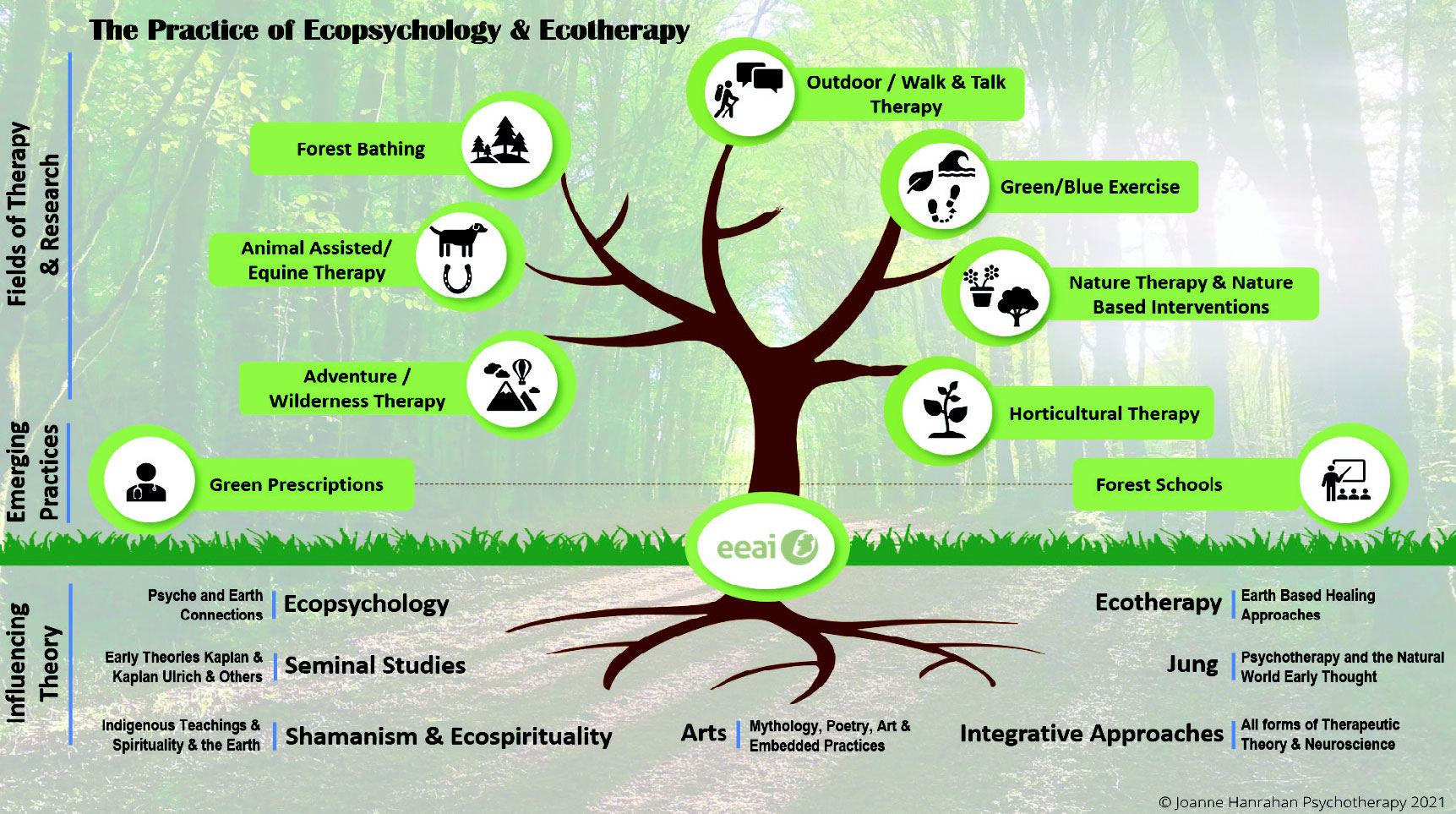

Additionally, systematic reviews completed in different parts of the world within various academic disciplines (Berto, 2014; Keniger et al., 2013; Heinsch, 2012; Hansen-Ketchum et al., 2009) have evaluated the body of research on human-nature contact. In all cases, the literature examined point to the psychological, cognitive, physiological, social and spiritual benefits of interacting with nature. Phenomenological and theoretical knowledge in relation to the human and other-than-human world has continued to expand into a multitude of disciplines. Those involved with the care of others, who are informed by these fields of research, are often referred to by the umbrella terms of ecopsychology and ecotherapy. The info graphic below in Figure 1 was designed for the Ecopsychology and Ecotherapy Association of Ireland (EEAI) to summarise some of the aspects related to the development and growth of this therapeutic field, with many of the activities having their own distinct branch of research.

Figure 1: Created by Joanne Hanrahan

Nature and psychotherapy research

While this large body of research highlights benefits of spending time in nature, it is only in more recent years that literature and empirical studies have begun to grow specifically in the area of psychotherapy and nature. A recent meta-synthesis (Cooley et al., 2020) of broad ranging outdoor therapeutic research, from therapy sitting on a park bench to therapeutic interventions on wilderness expeditions, provides an interesting summary of the therapeutic benefits of therapy outdoors. The authors conclude that taking therapy outdoors connects clients with nature, can enrich the therapeutic encounter, increase therapeutic creativity, mutuality, holism, freedom of expression and enhance practitioner wellbeing.

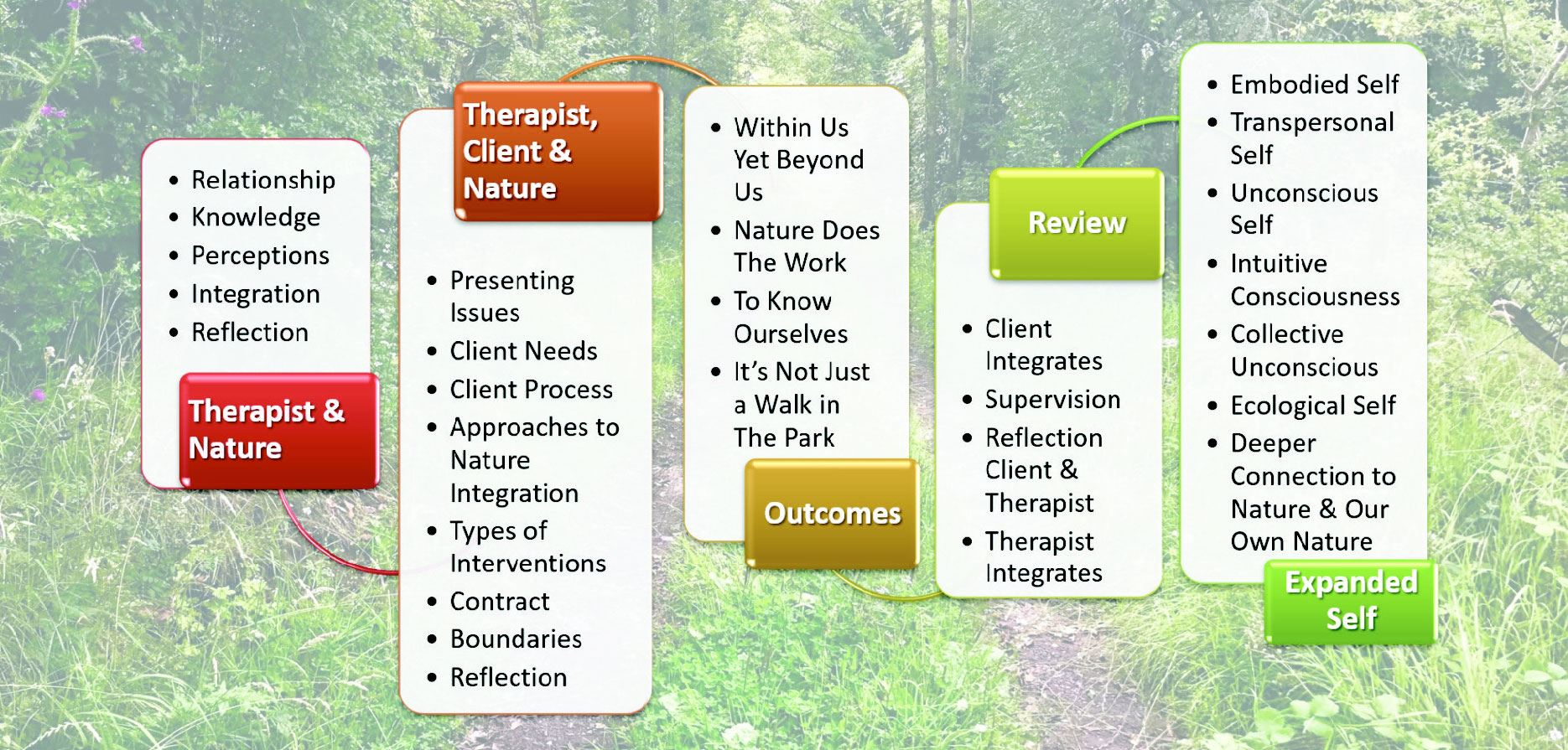

Focusing on one-to-one psychotherapy in Ireland, this author’s research (Hanrahan, 2015) and corresponding IAHIP conference paper (Hanrahan, 2016a), involved the analysis of qualitative data captured from nine Irish psychotherapists who integrated nature in a significant way into practice. The research findings highlighted five themes, introduced here. Theme names were derived from direct quotes from the research participants. Two themes, ‘Within us yet beyond us’ and ‘Nature does the work’ highlighted the numinous and often intangible aspects that nature brings to psychotherapy. These touch on spirituality, interconnectivity and feelings of awe, along with teachings from nature, symbolism, creativity, and meaning making.

Another two themes which emerged from the research ‘It’s not just a walk in the park’ and ‘To know ourselves’ explored reflective theoretical practice, what might be described as the nuts and bolts of therapy, and the deepening awareness of the client to their own psychological processes including embodiment through contact with nature.

Through the development of the themes Hanrahan (2015) further suggests that the integration of nature and psychotherapy has the potential to expand the self, with increased awareness of the transpersonal self, embodied self, and unconscious aspects of the self. Links are also made to Jung’s (1968) collective unconscious and concepts such as Hollwey and Brierley’s (2014) intuitive consciousness. Developed through research and extensive outdoor clinical practice, Figure 2 represents a framework for practice, as originally presented in Hanrahan (2016b).

Figure 2: Created by Joanne Hanrahan

Working outdoors, as with indoors, a therapist needs to be very grounded in their therapeutic approach and mindful of their own process. As highlighted in the diagram above, as with all approaches to therapy, outdoor therapists need to engage in reflective practice. While the British Psychological Society’s recently published guide The use of talking therapies outdoors (Cooley and Robertson 2020) is a very useful reference for new outdoor practitioners, it is widely recognised that the therapist’s own personal process in the natural world should be explored and reflected on before and throughout their practice with clients outdoors (Delaney, 2020; Jordan, 2015; Marshall, 2016). Therapists should also reflect on their competency, and seek training and supervision on their outdoor work (Hooley, 2016; Richards et al, 2020). As Carl Rogers proposed “neither the Bible nor the prophets – neither Freud nor research – neither the revelations of God nor man – can take precedence over my own direct experience” (Rogers, 2004: 24)

The final theme which emerged in Hanrahan (2015), ‘That’s not quite academic’, refers to a concern among participants that, while we as humans are all part of the natural world and nature is fundamentally resourcing, its integration into therapy seemed to be viewed with scepticism by many psychotherapy training schools and supervisors. This theme was more relevant at the time of the research than it is now, over five years later. The intervening years has seen a mushrooming in related academic research and literature (Brazier, 2018; Delaney, 2020; Harper and Dobud, 2020; Jordan and Hinds, 2016; McGeeney 2016; Rust, 2020) along with corresponding growth in international conferences - Confer 2016, 2018, 2019 - addressing the topic of Psychotherapy in the Natural World. This expansion and dissemination of knowledge has helped to bring outdoor psychotherapy and ecotherapy in from what may have been seen as fringe (Brazier, 2018) to more mainstream psychotherapeutic thought.

Reflection and setting the scene for outdoor clinical practice

While the above academic research has informed my approach, outdoor clinical practice since 2015 has inspired me and enriched my knowledge. I have witnessed the themes from my research and findings of other studies come to life through my practice with clients. While there is much to be discussed on the integration of nature and psychotherapy, given the global traumatic experience that the Covid-19 pandemic has brought, the focus for this article is the merger between outdoor psychotherapy and trauma informed approaches to therapy. Reference will be made to some of the overlap in the two fields of literature and to clinical vignettes from my own practice. All client details have been anonymised.

A critical aspect to working therapeutically is the client’s sense of safety. Given the differences from the traditional environment of working indoors, when taking therapy outdoors therapists should contract with their clients around confidentiality and privacy issues and discuss how they will deal with meeting other people (Brazier, 2018; Jordan, 2015; Jordan and Marshall, 2010). Clients should have a clear understanding of what they can reasonably expect at a given venue in terms of sitting versus walking options, how populated the area may be and the availability of private spaces within the terrain. Therapists should also review the route or venue in advance and assess its suitability.

When working indoors, the four walls of the room can act as part of the container of the process and creation of a safe space. However, when working outdoors the ‘containment’ for the work can be seen as coming from three different elements. Firstly, we can work with the client’s body as a container to track process and receive resource (Levine, 2015; Marshall, 2020). Secondly the environment works as a container and can be both implicitly or explicitly involved as a ‘co-therapist’ (Berger & McLeod, 2006; Jordan, 2015) or ‘living third’ (Marshall, 2016). Finally, the therapeutic relationship contains and coregulates the client (Dana, 2018; Jordan, 2015; Porges, 2011). Thus, the therapist’s own regulation in the environment is also a vital component of the work (Jordan, 2015; Marshall, 2020).

Nature therapy research and trauma informed practice

The concept of resourcing our clients and ‘titrating’ (Levine, 2015) or dosing trauma work, little by little, while helping clients increase awareness of the felt sense (Gendlin, 1996) in their bodies is important in trauma informed approaches to therapy. This helps our clients build capacity by experiencing some dysregulation while staying within their window of tolerance (Levine, 2015; Siegel, 2010). Since trauma is not what happened to us but how the body responds to that event (Levine, 2015; Mate, 2019; van der Kolk, 2015), an understanding of psychophysiology is useful when working with trauma. The following is a brief introduction to this topic.

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) has long been understood to have two main branches known as the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems. However, Porges’ polyvagal theory (Dana, 2018; Hegarty, 2020; Porges, 2011) with its organising principles of autonomic hierarchy, neuroception, and co-regulation, has brought new and exciting insight into our understanding of psychophysiology. Porges’ theory on the ‘autonomic hierarchy’ further increases our knowledge of two subparts of the parasympathetic, the dorsal vagal and the ventral vagal. All aspects of our ANS are vital to our day-today functioning; however trauma, which involves high levels of stress in the body, may initiate survival responses. Chronic hyperarousal of the sympathetic system results in fight or flight responses while the survival response of the dorsal vagal results in freeze or shut down.

Of enormous benefit to the world of psychotherapy is increased awareness of the ventral vagal system. The ventral vagal system, which is found only in mammals, supports social engagement and connection and is the part of the ANS where we can feel calm and relaxed. In trauma informed practice it is now widely recognised that clients need to have increased access to, and practice of, returning to or “anchoring” (Dana, 2020: 33) in the ventral vagal system. Dana describes resilience as “the ability to return to ventral vagal regulation following a move into sympathetic mobilisation or dorsal vagal shut down” (2020: 37). Dana also describes experiences of awe, creativity, joy, excitement, interest, alertness, ease and rest as central to accessing the ventral vagal aspect of our ANS. Interestingly, considering its rise in popularity, literature suggests that through stimulation of the sympathetic aspect of the ANS, and a corresponding increase in tolerance to stress responses, cold water swimming or immersion can have a positive effect on our psychological wellbeing (Dana, 2020; van Tulleken et al., 2018).

So how does recent psychophysiology research fit with our connection with nature and the practice of psychotherapy? Throughout the large body of research on the interaction between humans and the other-than-human natural world, the resounding message is that contact with nature, even virtually, can bring ease to our physiology (Berto, 2014). Nature’s physiological resourcing properties are well documented. Increasingly, there are mergers in the literature highlighting the importance of nature-based interventions in trauma work (Delaney, 2020 cited in Arcuri Sanders & Forziat-Pytel, 2020; Berger & Lahad, 2013; Linden & Grut, 2002; Marshall, 2020). In her teachings, Dana (2020b) frequently refers to how even calling up images in our minds of our favourite places in nature can bring us increased ventral vagal tone. In a further validation of the author’s research (Hanrahan, 2015) and ongoing clinical practice, Dana encourages therapists to consider the potential of a room with a view, mindful attention and soft focus on natural materials in the room, nature-based homework, and she prompts therapists to “consider moving outside” (2020: 136) for sessions.

Trauma informed outdoor clinical practice vignettes and personal reflection

Trauma can be defined as “an emotional response to an intense event that threatens or causes harm. The harm can be physical or emotional, real or perceived” (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014: 2). There is no doubt that the Covid-19 pandemic, and all that it has brought, can be described as a traumatic event on a global scale. All of our lives, therapists and clients alike, have been affected and catapulted into the unknown. The Covid-19 emergency not only evoked a new and unique trauma but ignited in each of us our own trauma pattern of our old personal survival responses.

Knowing how important it was to try help my clients regulate their nervous systems and trusting the well-established regulating properties of the natural world, I offered all my clients the option of outdoor sessions as lockdown restrictions lifted in May 2020. While the online option was still available to them, 100% of my clients, including ones with no experience of outdoor therapy, chose to go outdoors. The first obvious benefit seemed to be social engagement. Far from worrying about the possibility of meeting someone they knew, clients seemed to relish in the experience of not just meeting me face to face but actually seeing other people or evidence of them. Tom, an older client who, post-lockdown, had just come out of ‘cocooning’, chose to have his entire experience of therapy in a local woods on a public trail. On outdoor sessions he reflected ‘In this time of Covid-19, it has a slight social element in that you see others, smile and say ‘Hello’. This is also reminiscent of Treisman’s (2020) suggestion that “every interaction can be an intervention” and the importance of the smiles and the ‘neuroception’ (Porges 2011; Siegal 2010) experience of cues of safety. Tom’s sensory experiences and slowing down in the forest became a really important part of his therapy and he reflected that it ‘makes you aware of your inner self and how you relate to your surroundings’.

Sophie, who lives alone, also remarked on how the outdoor sessions post-lockdown allowed her to see ‘a passing moment in other peoples’ lives’ and to have an ‘awareness outside my bubble’. She also got great pleasure from watching a community ‘beach rock art’ initiative develop on a sea wall ‘gallery’. As we looked at the art pieces together, I was reminded of lines of Mary Oliver’s poem Wild Geese:

You do not have to be good. You do not have to walk on your knees for a hundred miles through the desert repenting. You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

(Oliver, 1986: 14)

These lines always remind me that therapy doesn’t have to be hard, in fact the opposite is true. Regulation and co-regulation can include movement, play and joyful engagement (Perry, 2020; van der Kolk, 2015).

Peter struggled to get up out of bed to his laptop on the kitchen table for our online sessions throughout lockdown. Dorsal freeze, exhaustion and shut down is a familiar pattern for him, albeit exacerbated by lockdown. Despite us both getting used to the online therapy format and having some profound work and moments of meeting on that platform, I was very cognisant of what the outdoor sessions brought. As with many of my clients Peter would have a history of developmental trauma and attachment ruptures. Kain and Terrell (2018: 179) state that the “treatment plan for working with such clients could be summarised as follows: regulation, regulation, regulation …. and then more regulation”. As with most clients, the natural world was very resourcing and regulating for Peter. All our outdoor sessions involved walking for the hour. Through movement, and drawing his attention to the felt sense of movement, Peter was able to experience some healthy sympathetic charge and mobilisation and also have access to increased ventral vagal tone. The importance of movement and rhythm in nervous system regulation (Levine, 2015; Perry, 2020; Treisman, 2020) informed my sessions with Peter and others. Along with the clients’ gait, pace and my own somatic resonance I am conscious of the “movement signature” (Marshall 2016: 152) of my clients.

Maria struggled to get out of her head; she longed for answers and certainty. The Covid-19 crisis was intensifying her feelings around lack of control and her system was increasingly dysregulated. In the therapy room, I had a sense of her body holding a lot of tension. Her increased ease in her body in outdoor sessions always struck me. Maria, drawn to the sea, had a particular place where she liked to sit for our sessions which we called the ‘office’. One day after the first lockdown when we were at the ‘office’ she remarked on a flat rock where the sun was shining, just below us, and how she would love to lie there in the sun. Informed by the Somatic Experiencing (SE) mantra to ‘orient to pleasure’ (Dunlea, 2019; Holzmann, 2015) in order to down-regulate activation and savour an experience in an embodied way, I asked her if she would like to try lying on the rock. I was delighted that she took me up on the suggestion. She lay out, eyes mostly closed, for most of the rest of the session, while I sat beside her gently encouraging a deep felt sense of ease. Van de Kolk (2015) advocates therapeutic experiences that can restore a sense of physical safety and I would see this as one such example. Maria felt totally held by the environment, was able to connect with sensations of safety in her body (Dunlea, 2019; Levine, 2015) and had increased access to both parasympathetic aspects of the nervous system, ventral vagal and healthy dorsal vagal. Healthy dorsal vagal is essential for our rest and digest functions and prosocial bonding (Dana, 2020; Porges, 2011). Kain and Terrell (2018) explain that the dorsal system’s support of prosocial behaviours occurs with experiences of what Porges refers to as ‘immobility without fear’. My hypothesis is that this may have been such an occasion for Maria. My role felt like the guardian of the space and Maria trusted me to witness and help her truly embody this experience of safety. As we walked to our cars, at the end of the session, she joked about our new version of Freud and his couch. Sometime later she recounted the session and described how her experience that day, being out in nature with me, had allowed her to feel ‘soothed’ and ‘less inhibited’. When we connect with others and “take time to appreciate our connection to the natural world around us, we activate and reinforce the brain’s relational circuitry” (Siegal, 2017).

Melissa sat looking out to sea for one of her sessions. I watched with interest as she seemed to ‘titrate’ (Levine, 2015) her own trauma story. The environment helped her move from speaking of her early trauma, to a pleasant memory on a boat with her grandfather and then to bringing her to the present moment. Later she reflected ‘when we are outside, getting blasted by sea air and passed by low flying sea gulls it makes me realise that I’m here, not in that moment again and that I’m safe’. This anchoring in the present moment in nature is very helpful when working with trauma (Linden & Grut, 2002; Marshall, 2020).

Another client, Jenny, also referred to her outdoor sessions using the term safe, saying that they ‘have also created new safe spaces for me, because I was there with you, whom I trust, and I worked through hard things there’. The creation of the safe space in nature where clients can return without the therapist is also evident in the literature (Berger, 2008; Jordan, 2015). For many clients, outdoor therapy and walking side by side feels less threatening and less intense than experiencing the human gaze sitting in a therapy room or engaging in online therapy (Brazier, 2018; Jordan, 2015; Marshall, 2020). It can also enhance the therapeutic relationship in many ways. When reflecting on taking therapy outdoors, Jenny also remarked that ‘because we are both out in the world experiencing the same new inputs, it is more of a shared experience than a clinical one’. Similarly, Conor felt it ‘removed some of the intimidation I felt when entering a dedicated therapy space’ and John remarked how it was easier to ‘talk about things I was embarrassed about’.

Barrows and Marshall (2020) review the important processes of working therapeutically in nature using ‘5Rs’; Relax, Receive, Remember, Release and Resource. While many of these aspects of process can be seen throughout this article, I feel it would be remiss of me not to now give some focus on the fact that contact with nature can also unearth trauma. This is what Barrows and Marshall refer to as ‘remember’. When working outdoors clients may come in contact with disassociated parts more quickly (Hanrahan, 2015; Linden & Grut, 2002; Marshall 2020; Marshall, 2016). This may be through sensory triggering and also the increased access to the sub-symbolic (Bucci, 2008) processing. In my own client work, one such example stays with me. On an outdoor session my client Patricia and I passed a farm yard. Personally, I smelt silage which was not disturbing to my system. Patricia however became overwhelmed by her sense of smell feeling physically sick. It was a short walk to the beach where Patricia could regulate. It was only after the session that I felt I had a hypothesis on what had been unearthed from Patricia’s unconscious process. She had nursed her father who died of colon cancer and I believe something of that trauma was evoked through her senses and a smell she perceived as repugnant. In these moments, therapists need to use their skills to explore the emerging process even if the specific trauma is not in conscious awareness, and use the natural environment to ground and regulate themselves and co-regulate their clients (Jordan, 2015; Marshall, 2020).

Conclusion

This article has introduced the reader to some of the background research which supports the view that the natural world is restorative and that outdoor psychotherapy has many benefits. Choosing, for the purpose of this paper, to review the literature and my practice through a trauma lens, I have highlighted some of the links between trauma informed approaches to therapy and literature on outdoor psychotherapy and ecotherapy. I hope that, through encountering many of my clients’ stories and feedback of their experience as clients in the outdoors, more Irish therapists will be encouraged to embrace this exciting new way of working. Hollwey and Brierley (2014) suggest that the numinous realm and psychological science are essential parts of our existence and need a reliable bridge to join them. I would suggest that nature and its integration into psychotherapy may provide one such bridge between science and soul.

Finally, I will return to my title, a quote from Susan, my first ever outdoor client in 2015. Susan lived with cancer and her grandchild had just been born with a disability. She found it profoundly moving when she slowed down to listen to the birds and notice that in harsh conditions they were still singing. Let’s hope through Covid-19 and beyond, we too, can continue to sing.

Joanne Hanrahan is a psychotherapist, trauma specialist, trainer and keynote speaker. She is accredited by IAHIP. Joanne completed her MSc on the Integration of Nature and Psychotherapy and has spoken internationally on the topic. She currently provides therapist training on outdoor psychotherapy. www.joannehanrahan.ie

References

Arcuri Sanders, N.M. and Forziat Pytel, K. (2020). Nature-based interventions for the military/veteran population. IN: Delaney, M.E. (ed.) Nature is nurture: Counselling and the natural world. Oxford University Press.

Barrows, G. and Marshall, H. (2020). Working in the field: An introduction to Eco-TA. Workshop, Online.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature therapy: developing a framework for practice. PhD thesis. University of Abertay, Dundee.

Berger, R. and Lahad, M. (2013). The healing forest in post–crisis work with children: A nature therapy and expressive arts program for groups. Jessica Kingsley.

Berger, R. and McLeod, J. (2006). Incorporating nature into therapy: a framework for practice. Journal of Systemic Therapies. 25(2), 80-94.

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioural Sciences, 4(4), 394-409.

Brazier, C. (2018). Ecotherapy in practice. A Buddhist model. Routledge.

Bucci, W. (2008), The role of bodily experience in emotional organisations: New perspectives on the multiple code theory. IN: Sommer Anderson, S. (ed.), Bodies in treatment: The unspoken dimension.

Child Welfare Information Gateway (2014). Factsheet for families: Parenting a child who has experienced trauma. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/child-trauma.pdf

Cooley, S.J., Jones,C.R., Kurtz, A., and Robertson, N. (2020). ‘Into the wild’: A meta-synthesis of talking therapy in natural outdoor spaces. Clinical Psychology Review, 77.

Cooley, S.J. and Robertson, N. (2020). The use of talking therapies outdoors. The British Psychological Society. https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/www.bps.org.uk/files/Policy/Policy%20-%20Files/Use%20 of%20talking%20therapy%20outdoors.pdf

Dana, D. (2020). Polyvagal exercises for safety and connection: 50 client-centered practices. W.W. Norton Dana, D. (2020b). Looking through the lens of polyvagal theory. Workshop, Professional Counselling and Psychotherapy Seminars Ireland.

Dana, D. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. W.W. Norton.

Delaney, M.E. (2020). Nature is nurture: Counseling and the natural world. Oxford University Press.

Dunlea, M. (2019). Bodydreaming in the treatment of developmental trauma: An embodied therapeutic approach. Routledge.

Frank, A. (1954). The diary of Anne Frank. Pan Books

Gendlin, E.T. (1996). Focusing-oriented psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

Harper, N.J. and Dobud,W.W. (eds) (2020). Outdoor therapies: An introduction to practice, possibilities and critical perspectives. Routledge

Hanrahan, J. (2015). Come away o human child to the waters and the wild: A qualitative study into the role nature can play in psychotherapy. MSc thesis. Dublin City University. www.joannehanrahan.ie/nature-therapy

Hanrahan, J. (2016a). Come away o human child to the waters and the wild: A qualitative study into the role nature can play in psychotherapy. Conference paper IN: Book of presentations and workshops from the IAHIP conference 2016. Keeping psychotherapy relevant to these changing times. https:// iahip.org/main_content/uploads/2016/09/OP363-IAHIP-Book-1.pdf

Hanrahan, J. (2016b). It’s not just a walk in the park: A research based perspective and emerging model on integrating nature into therapeutic practice. Conference paper for CONFER Psychotherapy and the Natural World conference 2016 UK. www.joannehanrahan.ie/nature-therapy

Hansen-Ketchum, P., Marck, P. and Reutter, L. (2009). Engaging with nature to promote health: new directions for nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(7), 1527-1538.

Hegarty, D. (2020). Polyvagal-informed trauma therapy: An overview. Inside Out, 91, 40-46.

Heinsch, M. (2012). Getting down to earth: finding a place for nature in social work practice. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21, 309-318.

Hollwey, S. and Brierley, J. (2014). The inner camino: a path of awakening. Findhorn Press.

Holzmann, M. (2015). Somatic healing nature and empowerment: An interview with Maria Holzmann. http://www.thebreathenetwork.org/somatic-healing-nature-empowerment-interview-maira-holzmann#:~:text=Orienting%20to%20pleasure%20is%20about,someone)%2C%20actual%20 behaviors%20(smiling

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical considerations for psychotherapy in natural settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4), 215-221.

Jordan, M. and Hinds, J. (eds) (2016). Ecotherapy: theory research and practice. Palgrave.

Jordan, M. (2015). Nature and therapy: Understanding counselling and psychotherapy in outdoor spaces. Routledge.

Jordan, M. and Marshall, H. (2010). Taking counselling and psychotherapy outside: destruction or enrichment of therapeutic frame? European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling, 12(4), 345-359.

Jung, C.G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Routledge.

Kain, K.L. and Terrell, S.J. (2018). Nurturing resilience: Helping clients move forward from developmental trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 169-182.

Kaplan, R. and Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Keniger, L.E., Gaston, K.J., Irvine, K.N. and Fuller, R.A. (2013). What are the benefits of interacting with nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 913-935.

Levine, P.A. (2015). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Linden, S. and Grut, J. 2002. The healing fields: working with psychotherapy and nature to rebuild shattered lives. Frances Lincoln Limited.

Marshall, H. (2020). An elemental relationship: Nature-based trauma therapy. IN: Chesner, A. and Iykou,

S. (eds.) Trauma in the creative and embodied therapies: When words are not enough. Routledge.

Marshall, H. (2016). A vital protocol: Embodied-relational depth in nature-based psychotherapy. IN:

Jordan, M. and Hinds, J. (eds) Ecotherapy: theory research and practice. Palgrave.

Mate, G. (2019). When the body says no: The cost of hidden stress. Ebury Publishing.

McGeeney, A. (2016). With nature in mind: The ecotherapy manual for mental health professionals. Jessica Kingsley.

Oliver, M. (1986). Dream work. Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Perry, B. (2020, August 25). Stress, trauma, and the brain: Insights for educators. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=cNzkyFPA7Lc&t=310s

Porges, S.W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neuro-physiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication and self-regulation. W.W. Norton.

Richards, K., Hardie, A. and Anderson, N. (2020). Outdoor mental health interventions: Institute for outdoor learning statement of good practice. https://www.outdoor-learning.org/Portals/0/IOL%20 Documents/Outdoor%20Mental%20Health/Outdoor%20Therapy%20Statement%201.3%20-%20 12%20Oct%202020.pdf?ver=2020-11-09-101048-717

Rogers, C.R. (2004). A therapist’s view of psychotherapy: On becoming a person. Constable and

Robinson. (Original work published 1967).

Rust, M.J. (2020). Towards an ecopsychotherapy. Confer Ltd.

Sempik, J., Hine, R. and Wilcox, D. (eds.) 2010. Green care, a conceptual framework, a report of the working group of the health benefits of green care, COST Action 866, green care in agriculture. Loughborough: Centre for Child a Family Research, Loughborough University.

Siegal, D.J. (2017). The healthy mind platter. https://www.drdansiegel.com/resources/healthy_mind_ platter/

Siegal, D.J. (2010) The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. W.W. Norton.

Treisman, K. (2020, April 9). Every interaction can be an intervention. https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=8pBkXbCP3Q4&feature=youtu.be

Ulrich, R.S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 224(4647), 420-421 Van der Kolk, B.A. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Van Tulleken, C., Tipton, M., Massey, H. & Harper, M.C. (2018). Open water swimming as a treatment for major depressive disorder. British Medical Journal. DOI:10.1136/bcr-2018-225007

Wilson, E.O. (1984). Biophilia-The human bond with other species. 12th ed. President and Fellows of Harvard College.

IAHIP 2021 - INSIDE OUT 93 - Spring 2021