Supporting the human being within healthcare workers: Facilitating staffSPACE, a Process Oriented Psychology-informed approach

by Pádraig Cotter

This rhetoric has created a divide between healthcare workers and human beings and has overlooked the degree to which the healthcare worker is also a human being. Society has had a strong need to see this group as ‘special’ because society has had a strong need for this group to look after it and keep it alive. A very significant helper role has been projected onto healthcare workers allowing little space for how they are also just people. This societal polarisation has been internalised by many in healthcare roles and has created a lot of unconscious or unseen distress for healthcare workers.

The importance of looking after healthcare workers or the need for ‘helping the helpers’ has been well-documented (McCann et al., 2013; Maslach & Leiter, 2018; Todaro-Franceschi, 2012; Vaithilingam et al., 2008). This is even more pertinent in the current climate given the additional demands created by the Covid-19 pandemic. This paper outlines one means of supporting the ‘human being’ within frontline healthcare workers. What follows is informed by learnings from Mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 2018), Person-Centred Therapy (Rogers, 1957), Group Psychotherapy (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005), Existential Psychotherapy (Yalom, 1980) and in particular the group and systemic application of Process Oriented Psychology (POP) (Mindell, 1995; 2014). It describes a way of providing frontline staff with a space to process different aspects of their experiences, especially those that have been marginalised within other areas of their lives and by society at large.

Formulation

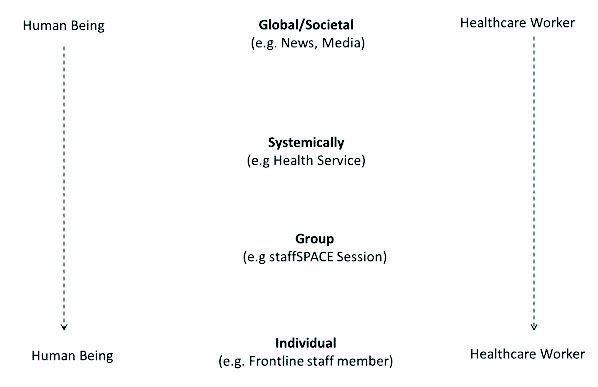

There are multiple levels or components to the issues faced by frontline staff (Figure 1). Staff may be experiencing anxiety at an individual level within their own life, as well as increased anxiety within their families, within their workplace and within society more generally. Bringing awareness to the anxiety at each of these levels normalises the experience of anxiety at an individual level. Where this is not done, and the anxiety is formulated at only an individual level - where thoughts and feelings are constellated within the individual - the person is not relieved of the group, systemic and societal aspects of ‘their’ anxiety.

Acknowledging and normalising the nature of the anxiety in the world is important. There is increased anxiety across the globe because there is good reason for people to be anxious. Never in living memory have human beings been forced to confront major existential fears in such an immediate and collective manner. The anxiety surrounding death has rarely been as present. It is important to acknowledge this anxiety and formulate it as an expected experience in the current circumstances.

From an evolutionary perspective, it is necessary to acknowledge that the anxiety people are experiencing is also needed - as something that will help keep people alive. It supports individuals to comply with the types of measures that will prevent themselves and others from dying.

Given the collective nature of anxiety inherent in the world at present, a group-based intervention is well-suited to exploring these issues.

Figure 1. Healthcare worker-human being dynamic at a global, systemic, interpersonal and intrapersonal level.

The staffSPACE interventionThis is a practice-based intervention that facilitates staff in Stopping to Process And Consider Events (SPACE). It has been used within a broader staff support programme (Cotter et al., 2020). It can be done with a group of healthcare workers expressing a wish for support.

Preparatory work.The first step involves the group facilitator doing their own inner work. It is important to think about the roles that are likely to emerge within the session and how they relate to the facilitator. A starting point may be to consider how the role of ‘healthcare worker’ and ‘human being’ are part of one’s own life. Consider them as roles that exist externally and at an intrapersonal level.

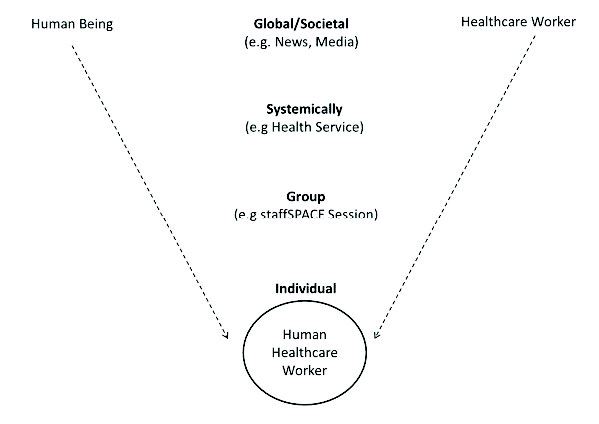

If the facilitator plans on co-facilitating with someone else, this would be best done with one’s co-facilitator. If the reader finds themselves resisting this personal work, it is important to explore the resistance. Figure 2 and Box 1 depict the author’s inner work completed as preparation for facilitating staffSPACE sessions with healthcare workers in an acute adult inpatient mental health setting.

Figure 2. Healthcare worker-human being dynamic at a global, systemic, interpersonal and intrapersonal level - after processing the roles.

It is also useful to consider other roles that may emerge in such a group as well as the sub-roles that may exist under the broad umbrella of healthcare worker and human being. In particular, attention is required to the ones that may hold some kind of emotional weight or value in one’s own life.This type of inner work would also be useful for working with healthcare workers at an individual level. There is one micro-intervention that can be deployed in any individual exchange with frontline staff - ask them about their home life. It could be about their loved ones, their families, or how they are coping. Small interventions such as this can go some way to offsetting the polarisation described above.

|

Example of Inner Work |

Box 1. Reflecting on the healthcare worker-human being dynamic at an intrapersonal level.

Introducing staffSPACE

At the start of a session, the facilitator creates a clear opening to the group process (e.g. Box 2). They might bring awareness to some of the issues mentioned in the introduction and other related issues. It is useful to be mindful of posture, tone and pace of speech and to use them to cue the group into it being a reflective space. Key issues such as confidentiality are discussed and everyone is invited to say their name. Reciting one’s name can help people to find their voice and may make it easier to speak later on.

|

‘Welcome everyone and thank you for coming. This is our staffSPACE session. We want to recognise the many demands that are being placed on staff at the moment. We recognise that there are many demands here at work (the healthcare worker role) and that there are many demands outside of work (human being role). Covid-19 is generating a lot of stress and anxiety for all of us and this session is designed to give staff a space to process some of those anxieties and challenges, while also allowing space for people to discuss things that may be going well. It is for the group to use the session as it needs, and this may change from day-to-day. It is important to say that this is a confidential space and the group discussions are not fed back to senior management in any way. If the group decides that there are things that need to be actioned as a result of the discussion, then it is up to the group to decide how it wishes to do that.’ Opening Mindfulness Exercise ‘Ok so let’s start then. Just pay attention to your breathing and notice the in-breath… and the out-breath… Notice the flow of air on the bottom of the nostrils. Feel the air as it comes in and out… in and out… in and out… (continue as needed) Notice any thoughts and feelings that arise… You’ve all likely had a busy morning so far, with lots of demands being placed on you in various different ways. Just notice the thoughts and the feelings, acknowledge them and bring your awareness back to the next inhale… and exhale… In and out… in and out… in and out…(continue as needed). And now shift the awareness from the nose down into the belly. Watch the rise and fall of the belly with each inhale and exhale. In and out… in and out… in and out… (continue as needed). And now, take three longer and deeper breaths and when it feels right, open your eyes and come back to the room.’ Closing Mindfulness Exercise ‘As we did at the start, allow the attention to fall on the breathing and notice the in-breath… and the out-breath… Notice the flow of air on the bottom of the nostrils. Feel the air as it comes in and out… in and out… in and out… (continue as needed). As you do, allow something to come to mind that emerged over the past hour that was meaningful for you or touched you in some way (This can be altered based on what emerged in the group. Other examples might include: one thing you appreciate about the team or your colleagues; or one thing that is important to you in your home life). Just notice whatever comes to mind, acknowledge it and then bring your awareness back to the next inhale… and exhale… In and out… in and out… in and out…(continue as needed). And now shift the awareness from the nose down into the belly. Watch the rise and fall of the belly with each inhale and exhale. In and out… in and out… in and out…(continue as needed). And now, take three longer and deeper breaths and when it feels right, open your eyes and come back to the room.’ |

Box 2. Examples of introductory and mindfulness scripts.

Opening mindfulness exercise

After the introduction, a brief mindfulness practice is narrated (e.g. Box 2). This is to create a separation between the regular demands of the working day and the reflective nature of the session; to bring people into the present moment; to become more aware of body, thoughts and feelings; and as a ritual to mark the beginning of the session.

The facilitator asks the group about the concerns that they would like to put on the agenda for discussion. The facilitator wants to get an idea of the issues without committing to discussing any one at this stage. These could be put on flipchart paper. As the facilitator goes around the room, new topics can be added or topics can be linked where that makes sense. It is helpful to use the group members’ words rather than reframing them and it is useful to get consensus before grouping topics. The facilitator does not want to spend too long sorting but long enough to get an idea of the issues in the room. The POP perspective suggests that no matter what topic is chosen, the most important underlying process will emerge.

To choose a topic, get consensus from the group. This can be done through a show of hands or voting.

Sometimes the group can convey consensus through the level of interest in a topic or the level of energy that a topic has raised. Where this occurs, and it seems like there is an unsaid consensus, it can be good to check with the group before proceeding. In the author’s experience of facilitating groups of frontline staff who work together on the same ward, the theme or topic often emerges quickly because the group is fairly homogenous and they face the same challenges. If the group is more heterogeneous with people coming from different aspects of a service, it may take longer.

Facilitating the process

Less may be more

Story-telling has been used by people as a way of coping with difficult situations since people were able to communicate (Payne, 2006). If the facilitator’s intervention offers little more than a space in which group members can tell their story, it will be hugely valuable. The very fact that this is being offered can help in giving staff a sense that the system is trying to look after them as human beings. The healthcare workers’ story may not get told at home because people at home may be distant with them for going to work. Equally so, work may be too busy, too demanding with an already too high level of distress for them to feel like they can tell their story there. Creating a space that is marked with clear rituals in which these stories can be told can be greatly needed. The POP perspective suggests that the wisdom is within the group. The facilitator does not have to create it or bring it with them. While every group will be different and will require the facilitator to respond in each moment, it may be true that less may be more, more often than otherwise.

Noticing the group atmosphere

It is important to pay attention to the unspoken and non-verbal atmosphere. The facilitator may pay attention to this as people are coming into the room, in the early exchanges and as the group progresses. It can help the group if the facilitator can notice an atmosphere or something at a feeling level that the group is less aware of. Bringing this into awareness can help the group to move forward, especially if it is cycling around an issue.

Framing

Framing and ‘weather reporting’ on different occurrences and exchanges is an effective intervention. This communicates to the group that the facilitator is following the process and keeping in touch with them. This may involve commenting or bringing awareness to something in a non-judgemental manner. It may also require the facilitator to summarise or paraphrase. One thing to be mindful of in terms of framing is when someone speaks at a personal level. It is important to bring awareness to this and offer the person support. When someone is speaking from a personal perspective it is important to be aware when other group members hastily return the conversation to a group, system or societal level. This can be hurtful for the person speaking and may make others feel unsafe about speaking personally.

Spotting roles

As the group unfolds it is useful to consider the roles or viewpoints that emerge. This is especially true where there are opposing or conflictual roles. Two of the likely roles (healthcare worker and human being) have been considered above. These may be evident within individual people as well as within the group.

Some people may identify strongly with the role of the healthcare worker and may disavow how they are also human beings. They may talk about the importance of their work with little reference to themselves or their home life. This may reflect the perspective projected onto them at a wider societal level. Other group members may be more identified with the role of the ‘human being’ and less focused on how they are healthcare workers. These people are more likely to talk about their stress, worries and anxieties; how they have a lot of concerns at home; and how work is making it difficult to manage. Some groups may be very one-sided, in one direction or the other, whereas others will have people representing each role.

Roles may vary significantly from group to group. The dynamic outlined above is one that the author has observed frequently, however it is also important to realise that the roles are also likely to change.

Sometimes, one group member may represent one specific role and the rest of the group the other role. Where this happens, it is helpful to bring awareness to how these are roles in the wider field so that no individual gets cast in that role in its totality. This is especially important if the role is seen as something negative by the rest of the group.

Bringing awareness to different roles can give people a chance to pick up aspects of their experience that have been marginalised. The author has observed a strong need for people to be able to express and pick up the human parts of their experiences while also validating, acknowledging and bringing an awareness to how they are ‘doing a great job’ as healthcare workers. Both are needed; the latter is being championed in many domains at present while the former is more likely to be overlooked.

Facilitating people to express themselves more fully can be replenishing and this can help in returning to the frontline. It can also have a longer-term effect in reducing the degree to which people become polarised or ‘split’ in trying to cope with the current circumstances. The more polarised people become, the longer it may take to eventually recover from the impact of this one-sidedness.

Spotting the missing role

Another important POP concept is the idea of a ghostrole or missing role. This is a role that is implicit in the field or group but has not been taken on or inhabited by anyone. The group could be talking about (or around) someone or something that is not being represented within the interaction but is having a significant bearing on the discussion.

At present, common ghostroles may include the government, politicians, local senior management, management at higher levels, or the Health Service more generally. People may be reluctant to express the ‘negative feelings’ they have towards these people. This is especially true when it comes to expressing unhappiness with local service management. The author’s experience has been that frontline staff are often angry with management because they do not feel like their efforts are being acknowledged appropriately. This is especially true, given the extra demands that are being placed on frontline staff and the significant additional anxiety caused by Covid-19. Welcoming in such missing roles can be very relieving for the group. Ghostroles are not always groups of people or a single person. They may also be an event or entity of some kind. At present, death and uncertainty are two likely ghostroles.

Where facilitators notice a ghostrole that is being ‘talked around’ it can be good to bring awareness to it. Doing this, in and of itself, can be relieving for the group. It can also be useful to represent it within the group. The facilitator can take on the role or use an empty chair to do so. This brings the missing role into the group and people can interact with it. It can be powerful for the group if the facilitator takes on the role of management or the government and says what the group feels has been unsaid in a heartful and meaningful manner (e.g. appreciating how everyone has all of their personal worries and is still coming to work). To do this however, it is necessary that the group gives the facilitator that role of the ‘appreciator’. It may also be influenced by the level of rank that the group attributes to the facilitator. For instance, the author is the only psychologist within the inpatient mental healthcare setting that he works in and therefore the system and staff afford him a certain degree of rank. It would not work if the system didn’t afford him that rank.

Negotiating hotspots

Hotspots are periods within the group process where something significant is occurring and there is a significant amount of emotional energy. This could be a moment of conflict, fight, flight or freeze, attack and defence, apathy, ecstasy or deep sadness. When the facilitator notices hotspots, it is important to bring awareness to them, frame them and support the group to slow down so that what’s occurring can be processed with awareness.

Bringing awareness to coolspots

Coolspots are moments of resolution, quiet reflective periods, a coming together between two opposing roles, or a significant shift in the group atmosphere to a sense of peace or stillness. It is important to bring awareness to coolspots as it is easy for the group to skip over them. Where coolspots are regularly skipped over it can feel like nothing really happened within a group process. Where facilitators can slow down and bring awareness to coolspots, it can anchor and expand any changes that may occur during such periods.

Closing reflection

It can be helpful for the facilitator to summarise some of the key issues that have arisen within the session. However, on other occasions the group process seems to bring itself to its own ending and an organic space emerges in which to introduce the closing mindfulness practice.

Closing mindfulness exercise

The closing mindfulness practice is as important as the opening one in terms of cuing the healthcare worker to the end of the session and preparing them to return to the frontline (Box 2). The author has found it useful to acknowledge the issues that have arisen within the group, in some way, within the mindfulness script.

Conclusion

Supporting healthcare workers by providing an opportunity to express both the professional and personal parts of themselves supports them in continuing to work on the frontline. Providing them with a space to process their concerns and anxieties, or perhaps lack thereof, is one way of doing this. Providing frontline staff with opportunities to process their experiences throughout the most intense periods of the pandemic may help them in coping with the ongoing anxiety and stress. This may also help in reducing the psychological impact of the crisis on them both during the crisis and in the longer term. Where this does not happen, people are more likely to become more polarised in how they cope and redressing this after the event will likely take longer.

References

Cotter, P., Jhumat, N., Garcha, E., Papasileka, E., Parker, J., Mupfupi, I., & Currie, I. (2020). A systemic response to supporting frontline inpatient mental health staff in coping with the COVID-19 outbreak. Mental Health Review Journal, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi. org/10.1108/MHRJ-05-2020-0026

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2018). Falling awake: How to practise mindfulness in everyday life. Hachette Books.Maslach, C. and Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, Vol 15 No. 2, pp 103-111.

McCann, C. M., Beddoe, E., McCormick, K., Huggard, P., Kedge, S., Adamson, C., and Huggard, J. (2013). Resilience in the health professions: A review of recent literature. International Journal of Wellbeing, Vol 3 No.1, pp 60-81.

Mindell, A. (1995). Sitting in the fire: Large group transformation through diversity and conflict. Lao Tsu Press.Mindell, A. (2014). The leader as martial artist: Deep democracy leadership in conflict resolution, community building and organisational transformation. Deep Democracy Exchange.

Payne, M. (2006). Narrative therapy (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). On becoming a person. HoughtonMifflin.

Todaro-Franceschi, V. (2012). Compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: Enhancing professional quality of life. Springer Publishing Company.

Vaithilingam, N., Jain, S., and Davies, D. (2008). Clinical Governance – helping the helpers: debriefing following an adverse incident. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, Vol 10, pp 251–256.

Yalom, I. D., and Leszcz, M. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (5th Ed). Basic Books.

Yalom, I. J. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

IAHIP 2021 - INSIDE OUT 93 - Spring 2021